Deductive Versus Inductive Reasoning

Reasoning can be an effective way to convince someone. You probably reason with others every day. For example, you may have to persuade your brother to share the last few sips of his strawberry milkshake. Two kinds of reasoning, deductive and inductive, illustrate why some methods of persuasion are more effective than others due to their basis in truth.

Deductive reasoning, also called top-down logic, starts off with a general statement, such as “All green plants need sunlight.” The next step is reducing the general to a particular example, like “This rosebush is a green plant.” Finally, you draw a conclusion: “Therefore, this rosebush needs sunlight.”

Deductive reasoning that is based on a general statement of fact is hard to argue with. When using this method, you begin with a factual statement that describes a class of things, such as animals. For example, you might say, “all animals need oxygen.” Because this is true of every animal, it is true of each animal as well. Therefore, you can truthfully conclude that a specific animal, like your pet gerbil, needs oxygen.

However, when the reasoning is faulty, deduction is open to debate:

- All cats are females.

- This tabby is a cat.

- Therefore, this tabby is a female.

Can you spot the flaw in the reasoning? Clearly, some cats are females but not all cats. You cannot reason that a particular tabby cat is a female based on your faulty generalization. The success of deductive reasoning depends upon the truth of your premise(“All cats are females”). A premise (a declarative sentence) is the basis for an argument. (More on logical argument here.)

When it’s not possible for the premise to be true and the conclusion to be false, you are looking at a valid argument.

- All cats are animals. [highlight highlightColor=”highlight-salmon” ]If this premise is true…[/highlight]

- This tabby is a cat.

- Therefore, this tabby is an animal. [highlight highlightColor=”highlight-salmon” ]… it is impossible for this conclusion to be false. Thus, we have a valid argument.[/highlight]

And when you have a true premise, you have the foundation for a sound argument.

- All cats are females. [highlight highlightColor=”highlight-lightblue” ]This premise is not true, thus we don’t have a sound argument.[/highlight]

- This tabby is a cat.

- Therefore, this tabby is a female.

- All cats are animals. [highlight highlightColor=”highlight-green” ]This premise is true, so we are able to build a valid argument to prove a conclusion.[/highlight]

- This tabby is a cat.

- Therefore, this tabby is an animal.

When you use deduction to come up with a valid and sound logical argument, you are offering up a deductive demonstration.

Inductive reasoning, or bottom-up logic, is the reverse of deductive reasoning. This method begins with specific pieces of information or observations, and then it concludes with a generalization that may or may not be factual:

- My bicycle has a flat tire.

- My bicycle is silver.

- Therefore, all silver bicycles have flat tires.

If you think this line of reasoning seems slightly off, give yourself a pat on the back. Inductive reasoning is rarely as sound as deductive reasoning because it leaps from limited experience to sweeping generalities:

- Every fire hydrant in my neighborhood is red.

- Every fire hydrant in my best friend’s neighborhood is red.

- Therefore, every fire hydrant in town is red.

The premises of inductive arguments do not prove their conclusions, but rather they support them. This is because the premises here are inferences. We are not certain if the inference is true or not. We want to make inferences that are more probable, as opposed to “risky” inferences. The strength of the argument depends on how strong the inference is. How probable does this inference need to be in order for us to accept the conclusion? The support for these inductive arguments lies in this area of “how probable” are these inferences. The less support provided, the weaker the argument. The more support provided, the stronger the argument. So the goal with inductive arguments is to be STRONG.

Deductive arguments have the goal of being VALID. If we have legitimate premises and then we draw the conclusion, we will know with certainty what is going on.

To recap, good logical arguments can come in two varieties: deductive demonstrations and inductive supporting arguments.

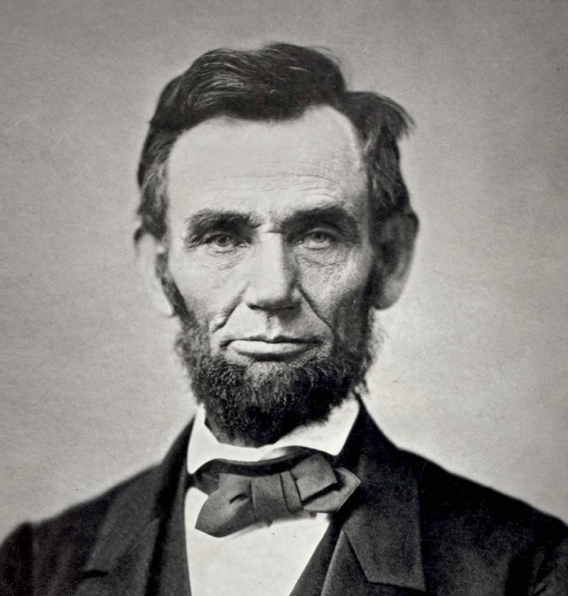

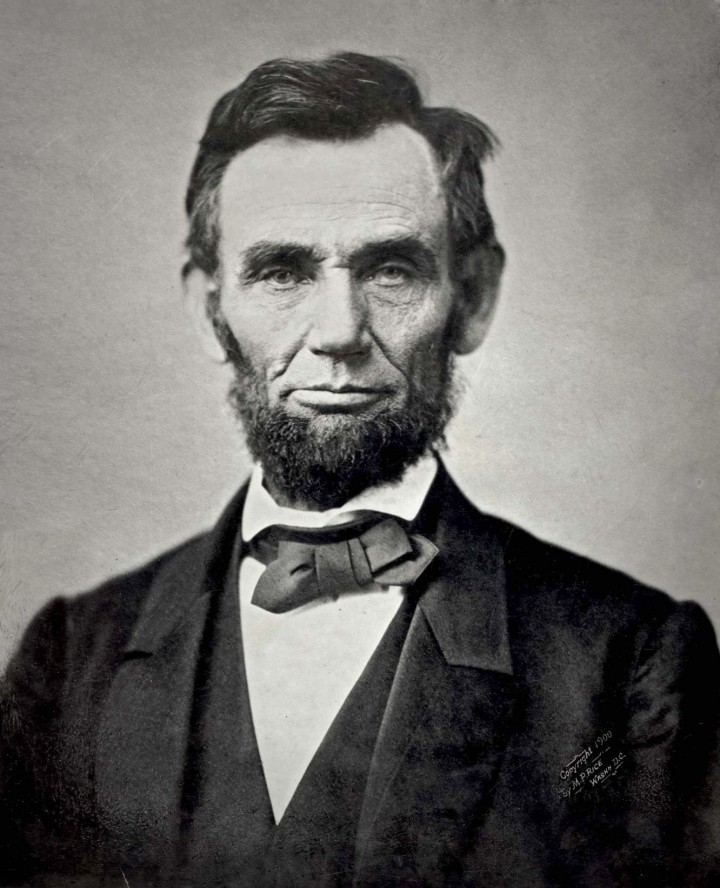

A Historical Example

In the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln found a fault in one of the premises that builds the argument below. Can you find the faulty premise below?

- Nothing in the Constitution . . . can destroy a right distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.

- The right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.

- Therefore, nothing in the Constitution can destroy the right of property in a slave.

Did you notice that number 2 is a faulty premise? Lincoln did too! He said: “I believe that the right of property in a slave is not distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.

- Nothing in the Constitution . . . can destroy a right distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.

- The right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution. (Not true; thus this is not a sound argument.)

- Therefore, nothing in the Constitution can destroy the right of property in a slave.

Today’s Activities for Kids: Deductions and Inductions

1. Look at the examples below and decide whether they are sound deductions.

- All first-graders are 6 years old.

- My cousin is a first-grader.

- Therefore, my cousin is 6 years old.

- All first-graders at Roosevelt Elementary take Spanish.

- Josh is a first-grader at Roosevelt Elementary.

- Therefore, Josh takes Spanish.

2. Create a logical conclusion based on the following examples of inductive reasoning. Then decide whether the reasoning is sound.

- This green jellybean tastes like spearmint.

- This green jellybean tastes like spearmint too.

- Therefore…

- I saw a man on a unicycle in the park last Sunday.

- I saw a man on a unicycle in the park this Sunday too.

- Therefore, next Sunday…