Arguments & Argument Maps for Kids

In day-to-day life “arguing” is usually understood to mean a disagreement or fight, and something that most try to avoid. But, in truth, arguments are part of critical thinking processes – part of how we use logical reasoning. The general structure for a logical argument is:

- This is my conclusion (or claim), it’s what I am trying to prove.

- Here is one premise that backs up my claim.

- Here is another premise that backs up my claim.

In logic, an argument requires a set of (at least) two declarative sentences (or “propositions”) known as the premises along with another declarative sentence (or “proposition”) known as the conclusion.

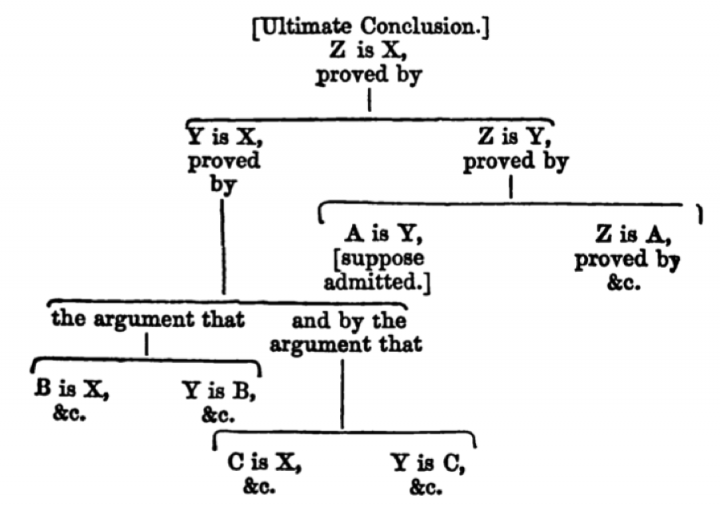

Argument Map (by John Wilkins)

Argument Map (by John Wilkins)

In 1826, Richard Whately published the Elements of Logic, and included what is probably the first form of an argument map. He noted “many students probably will find it a very clear and convenient mode of exhibiting the logical analysis of the course of argument, to draw it out in the form of a Tree, or Logical Division.”

There is empirical evidence that argument mapping improves critical thinking ability. Álvarez Ortiz’s meta-analysis found that argument-mapping-based critical thinking courses produced gains about twice as much as standard critical-thinking courses. His study used standard critical-thinking tests.

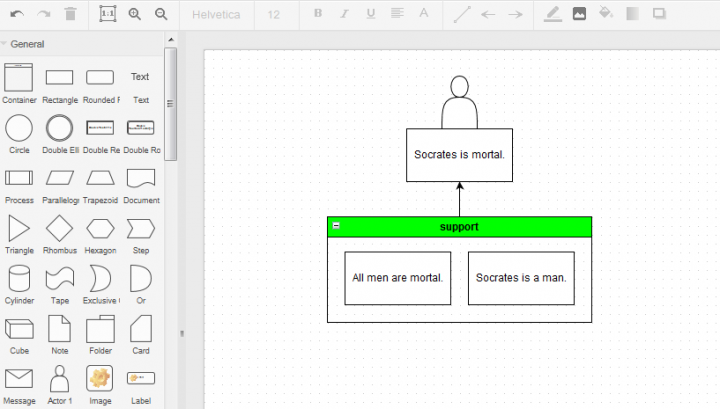

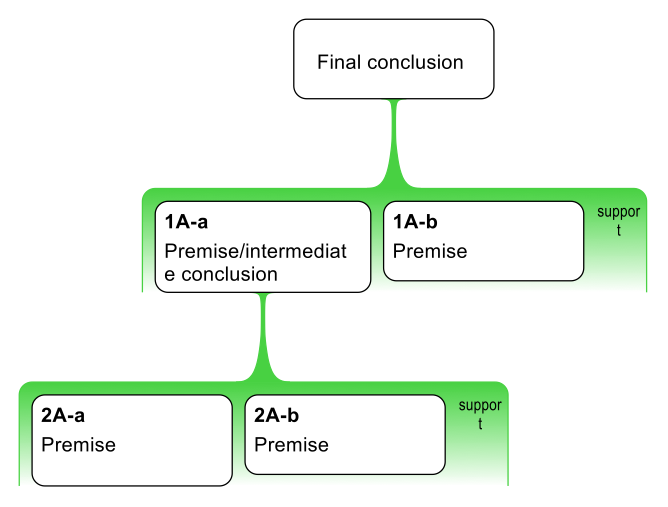

Below is an example of a simple argument map:

(credit: John Wilkins)

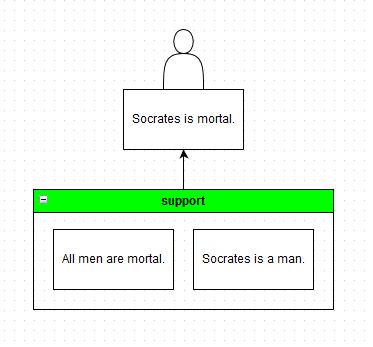

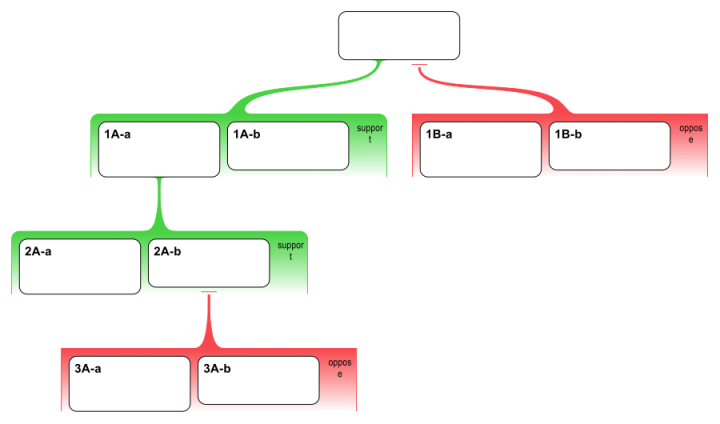

Here is an example of an argument map that includes objections in addition to support:

(credit: John Wilkins)

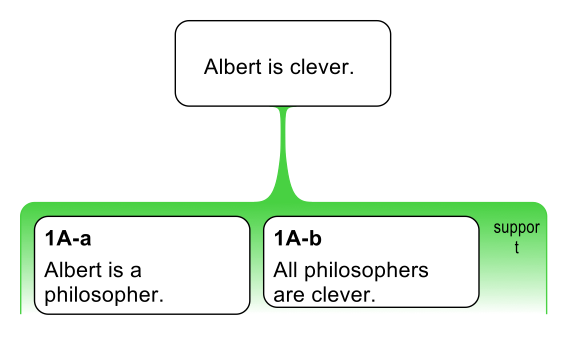

Try making your own argument map online with draw.io (example below). This works on the iPad as well!